Date: 3 Mar 2018 (Sat)

Time: 7.30pm to 9.00pm

Venue: The Buddhist Library, Level 2 Auditorium

View Video

Register Now!

“Even fifteen minutes of standing around doing nothing much was adequate. And although it seemingly had nothing to do with breathing, when I sat down at the end of a half-hour session, the breathing came to the fore unprompted.

It was a fuller kind of breathing: the experience was one of a steady energy tide that was associated with breathing, but wasn’t a matter of sensations – either that of the air brushing the nostrils, or of the push and pull of the diaphragm. It was a quiet steady energy that felt like it was breathing me. This ‘Qi’ energy wrapped gently and firmly around the mind and smoothed it out. Moreover as Qi, the breathing remained evident even when the sensations of breathing faded away (as they tend to when the mind calms down).

I reckoned that the Buddha, the embodied spiritual voyager par excellence, surely must have experienced this.

But where did he mention it? Looking through the Ānāpānasati sutta (M119), I paused over the term ‘bodily formation’ (kāyasankhāra). I always wondered what that meant. It is explained as ‘kāyasankhāra is in- and out-breathing‘ (M.44.14) – but that doesn’t go far: what aspect of breathing? Air? Sensation? Or what?

Sankhāra, one of the puzzle words of the Canon, crops up in many places, and is of crucial significance. As in the Buddha’s last words: ‘All sankhārā are impermanent, strive on with diligence’. And even more directly: ‘He turns his mind away from those states, and directs it towards the deathless element thus: “This is the peaceful, this is the sublime, that is, the stilling of all sankhārā, the relinquishment of all attachments, the destruction of craving, dispassion, cessation, Nibbana.”’ (M.64.9) Sankhāra is often translated as ‘formation’ or ‘fabrication’; but if sankhārā are ‘stilled’, they must be energetic. So how about rendering kāyasankhāra as ‘bodily energy’? In terms of direct experience that fits. The ‘bodily formation’ then is that bodily sense that one has when the eyes are closed and one isn’t focusing on external touch; it’s the internal sense that gives the impression of being in the body. Yes, that ‘forming’ is an ongoing activity (another way of rendering ‘sankhāra‘); it is a process whereby moment by moment, and centred on breathing, the body comes into awareness. Its energy is constantly fluctuating. And when you tune into it, it’s pleasant, and supports the ease and joy of absorption because it also regulates the mind’s energy. This bodily formation smoothes and brightens the mind through the bog of the hindrances. And as concentration deepens, you can feel that bodily formation change shape and texture. The body gets to feel light and like plasma, and of one texture rather than broken up into sections and twinges.

The Asian traditions have always understood breath to be much more than a respiratory matter: ‘prana’ – which must be some Sanskrit form of the ‘pāna’ of ānāpānasati – is the life-force which can be steered up the spine and through the entire body. So is Qi. In a similar vein, the Buddha describes the air element as ‘passing through the limbs’, something that respiration doesn’t do. So to the Buddha, breath is not just a lung and nose thing. And although my scholarship is rudimentary, experience affirms that. As the Ānāpānāsati sutta has it: ‘Thoroughly sensitive to the entire body, one breathes in and breathes out.’ Yes. ‘Calming the ‘bodily formation one breathes in and breathes out.’ Yes. Moreover, holding ‘energy’ as one aspect of what is meant by sankhāra also opens up a few other areas. If sankhāra entails energy, then ceasing isn’t annihilation of a thing, but the turning down of energy to a rest state. That makes nibbāna a little more accessible (at least conceptually). Just noticing that, as the body and mental energies quieten, the sense of wordless clarity and presence increases: that makes it more likely that nibbāna is a wiping clean, a voiding of differentiation, not a wipe-out of presence. And on a more rudimentary level, having a source of subtle and sustaining pleasure that is associated with calm and introspection helps to steer the mind away from external delights. ”

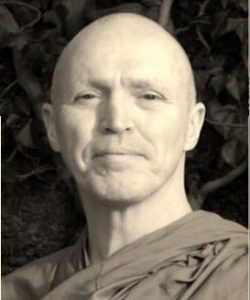

About Ajahn Sucitto

Luang Por Sucitto, 68, ordained since 1975, is a senior Western disciple in the tradition of Luang Pu Chah, the revered Thai meditation teacher. Retired from being the abbot of Cittaviveka, Chithurst Buddhist Monastery in 2014, Luang Por has given teachings worldwide and we are indeed privileged to have the opportunity to practice and receive guidance from the noble bhikkhu of 42 vassa